This post is our contribution to the WILLIAM WYLER BLOGATHON, running from June 24-29, 2012, and hosted by The Movie Projector. If you haven’t done so already, we urge you to visit The Movie Projector blog, one of the most intelligent and best-written classic-film spots on the Internet. And a number of great bloggers have signed up for the Wyler blogathon: You can view a list of these participating bloggers, with links to their posts, here.

We looked up William Wyler on the Internet Movie Database, and were struck, in the accompanying essay, by a statement about him—that Wyler is not regarded as an auteur. His work lacks a “signature” style—unlike, say, the films of Orson Welles, which, however variable their quality, have an unmistakably ‘Wellesian’ look. (No one, for example, would ever confuse the baroque camera work and expressionist cinematography of Welles’ 1952 Othello with anyone else—not even with Shakespeare.) A look at Wyler’s filmography might reinforce this non-auteur impression. His work ranges over a variety of genres, including literary adaptations such as Wuthering Heights, The Collector, Dodsworth, and Carrie; theatrical melodramas like Jezebel, The Letter, These Three, The Little Foxes, The Children’s Hour, and The Heiress; war films like Mrs. Miniver and The Best Years of Our Lives that deal not with warfare itself, but its effects on a pre- and post-war population; the romantic comedy Roman Holiday; the musical Funny Girl; the gangster film Dead End and the noir-like Detective Story (both also previously plays); and the blockbuster Biblical flick Ben-Hur.

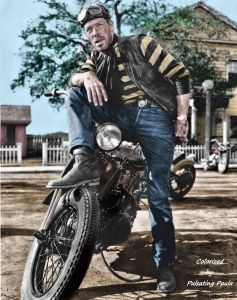

Wyler’s use of staging to create drama can be seen in this colored lobby card from ‘The Westerner.’ On left are stars Walter Brennan and Gary Cooper (who’s confiscating Brennan’s pistols).

One unifying feature of all these films, given the many theatrical and literary adaptations, is that Wyler’s movies themselves have a literate quality. There’s a respect for dialogue, for the way actors speak and interact, for the expression of ideas. One of our favorite scenes from The Little Foxes is two actors talking: Dan Duryea and Carl Benton Reid, as son and father, stand back to back, facing opposing shaving mirrors, as they discuss those bank bonds in that safe deposit box and how they can get their hands on them. Not that they actually come out and say directly what they mean. The dialogue is more a case of feints and dodges; the father questioning the son, hinting at his intentions, circling round, like a hawk sighting prey, without quite coming to the point. You need here actors who are able to structure a scene and build up to the punch; and you need a director who can give them the space and time to do just that. Wyler was said to be notoriously bad at communicating what he wanted from actors (forty takes on a scene was not unheard of), but a large, a really large number of actors who worked with him either won or were nominated for Oscars: Bette Davis, Fay Bainter, Walter Huston, Olivia de Havilland, Fredric March, Laurence Olivier, Greer Garson, Teresa Wright, Barbra Streisand, Ralph Richardson, Audrey Hepburn, Charlton Heston, Samantha Eggar, Harold Russell, and on and on. What might be called, if not Wyler’s signature, then certainly a stylistic trait—his use of long takes and deep focus—was one that, by arranging actors within the frame and allowing them to act without interruption, favored the performer.

That’s not to say that Wyler was ‘uncinematic’; it wasn’t a case of parking the camera in a convenient spot and letting the film roll while the actors acted. For example, the effectiveness of the above-mentioned scene from The Little Foxes is due in large part to how Wyler uses the cinematic frame. The posing of the actors (Reid watching Duryea’s reflection a mirror, or backing him into a corner) takes advantage of the screen’s boundaries, creating not just tension but the meaning of the two men’s interaction in confined space—their very proximity forces them into evasion. And recall the moment when a red-dressed Bette Davis in Jezebel first walks into the debutantes’ ball, how the space clears around her as the lines of properly white-clad girls sweep to the back and form a ring, simultaneously rejecting the defiant Julie and enclosing, and isolating, her within her transgression. This isn’t cinema for show (look what I can do with a camera, ma!), but as narrative psychology—it drives the story forward while inscribing, in movement and space, emotional truth.

Back to Back They Faced Each Other: Dan Duryea and Carl Benton Reid talk over their shoulders while thinking about bank bonds, in ‘The Little Foxes.’

Transgression: Bette Davis, in scarlet garb, and Henry Fonda are ringed by white-clad debs in back and the orchestra in front, in ‘Jezebel.’

All of this is a long preamble to our discussion of our Wyler film of choice, his 1940 opus The Westerner.

If you were to name a director of Westerns—which, just to make everything clear, The Westerner is—we bet Wyler wouldn’t be the first, nor even the second or third name you would bring up. That’s Ford’s country, isn’t it?—along with Hawks, Hathaway, Walsh, Mann, and Boetticher. It means scenes of big, expansive action—cattle drives kicking up dust, or the posse heading for the pass—or scenes of big, empty space—endless, flat plains ringed by far-off mountains, inhabited by hard, sinewy men with far-off eyes. People talk few words in Westerns, and what they do say is pretty straightforward—“Smile when you say that” is about as elusive as it gets.

But Wyler directed lots of Westerns, mainly a number of silent two- and five-reelers in the late 1920s; he was no stranger to the genre. His first talking film was the 1929 Western Hell’s Heroes; and one of his later films, The Big County (1958), was a prestige Western, with an A-list cast (Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker, Charlton Heston), plus an Oscar win for Burl Ives. Like the title says, the film is big—broad vistas of prairies and canyons and Heston’s bulging chest muscles. We tend to find The Big Country more bloated than big; it has a Message and clearly limned Good and Bad characters; and Mr. Ives gets to bellow a lot and even kick the furniture, which apparently impressed Academy voters.

Our own preference is for Hell’s Heroes; it’s leaner and meaner. Really mean. The film is an adaptation of Three Godfathers, a much-filmed story of outlaws rescuing a newborn child that most viewers, if they know it at all, probably know via John Ford’s sentimental 1948 Technicolor version. But perhaps, because it was an early Talkie and the industry was in flux, Wyler was willing to risk a thoroughly reprehensible character as the protagonist. In Wyler’s film Charles Bickford (who would later appear in The Big Country) plays the role taken by John Wayne in Ford’s version, that of the lead bank robber, but there’s little similarity. Wayne’s robber is a nice, jolly fellow who’s more than willing to save a helpless baby. But Bickford is a son of a bitch, who’d just as soon leave the infant to die in the desert. His very orneriness makes his redemption at film’s end all the more moving; he’s really been purged by his ordeal. And, unlike the pristine-looking The Big Country, the ‘29 film practically rubs our noses in the heat and aridity of the Old West. If the actors aren’t sweating, they’re crusted with dirt and dust, and seem to have been baked in the sun. Wyler gives us the real grit here; we can practically feel it in our skin and clothes as we watch.

Wyler’s use of framing within a frame: A dust-baked Raymond Hatton contemplates a possible destiny in ‘Hell’s Heroes.’

But even in this early film we can see Wyler’s use of the cinematic frame and the space within to give meaning. An example is the set-up for the bank robbery, which Wyler stages in a deceptively casual manner: One robber leading a horse crosses the screen while his three fellow robbers come riding up in the background. Wyler’s use of opposing directions—the flat, horizontal motion of the man with the horse, the depth created by the trio of robbers riding up into the frame—creates the tension for the action to come. And in the final scene, when a dying Bickford, with the child clasped to his chest, enters a church on Christmas Day and sinks to his knees, a number of arms and hands thrust themselves into the frame, surrounding the outlaw like an aureole of mercy, to take the child from his arms. Wyler compresses into this brief image not only compassion and succor but a metaphorical Christian redemption.

In between Hell’s Heroes and The Big Country falls The Westerner, and more than chronologically. Coming a year after John Ford’s Stagecoach, The Westerner partakes of that earlier film’s enlarging of the genre, reading more into the sagebrush saga than horses and shoot-’em-ups. Like Ford’s movie, The Westerner injects a mythic overtone, beginning with its opening credits: “Gary Cooper as The Westerner” is proclaimed across the screen, to erase any doubt of the title’s meaning. And Cooper’s Cole Harden is more than a character; he’s an archetype, a mythic representation in the essential American epic. Harden’s introductory shot, on horseback as his mount plods down screen center from back to front, encapsulates one of the Western’s basic plots: The Stranger From Nowhere, who stands between opposing forces in the yet-to-be-settled frontier, where rules don’t apply. It’s the overriding metaphor in both novel and film of Shane, in which the title character steps in between the feuding cattlemen and farmers; it’s present in Ford’s The Searchers, where Wayne’s Ethan Edwards straddles the divide between white settlers and indigenous Comanches; and it structures Wyler’s The Big Country, in which Eastern dude Gregory Peck becomes embroiled in familial range wars. And that divisional conflict sets up the series of oppositions that defines the classic Western narrative: Rancher versus Homesteader; Outlaw versus Lawman; Cowpoke versus Schoolmarm; Settlement versus Wanderlust; Wilderness versus Civilization.

As in The Big Country, The Westerner has its Outsider, here Harden, finding himself between two opposing forces: The raucous cattlemen, led by Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan), who condones their law-breaking behavior, and the recently arrived farm settlers, represented by Jane-Ellen Matthews and her father (Doris Davenport and Fred Stone), who insist on their right to the land. But Harden is also an ambiguous character, pulled between Bean’s freewheeling lawlessness and the Bible-reading Matthews’ sense of morality. He’s first seen, after the credits, riding into the Texas town of Vinegarroon, hands tied behind his back, with an escort that claims he’s a horse thief. Harden manages to clear himself of the charge—the real thief (Tom Tyler) fortuitously shows up and is shot down for his pains—but not until he encounters Jane-Ellen, who comes to town to discover one of her farm hands has just been hanged, and Judge Bean, the self-proclaimed “Law West of the Pecos,” who ordered the hanging. Cole himself is a man with no attachments: He has no past (asked where’s he’s from, he laconically replies “Nowhere in particular”) and an equally vague future (he’s heading to California to “see the Pacific Ocean.”). Harden’s movement throughout the narrative shifts between these two sides, which Wyler and his master cinematographer, Gregg Toland, inscribe into the film’s static frame and in their placing and movement of actors within that frame. (See at the end of this essay images from the film that illustrate this thesis.)

Although The Westerner foreshadows The Big Country in its narrative dichotomy, it harks back to Hell’s Heroes in its gritty portrait of frontier life. Bean’s saloon-cum-courtroom, for instance, is rickety and weather-beaten, practically reeking of bullets and bloodstains. (Bean, of course, was a real-life character, and the filmmakers took care to reproduce his real saloon.) In one shot of Harden riding out in the early morning, we can see a blanketed body lying on a porch, apparently having slept there the night. Both men and horses sweat in the heat; fighting men scrabble in the parched earth and raise a choking dust cloud; and Bean seems never to change his clothes.

The Rape of the Lock: ABOVE: Cole steals a lock of Jane-Ellen’s hair (he actually wants it to pass off as one of Lillie Langtry’s); Jane-Ellen looks both alarmed and interested. BELOW: Jane-Ellen smiles as she watches Cole store the lock in his wallet. Davenport’s facial expressions beautifully express her character’s conflicted feelings.

We may be in a minority here, but we’ll come out and say it: We prefer Walter Brennan when he’s a bastard. (Hey, that’s just us.) Most fans probably associate Brennan with his specialty, the comic, and unthreatening, garrulous old codger. He was never more garrulously old-codgeresque than as that toothless old geezer in Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo, screeching his lines between wheezes while badgering John Wayne like a senile nanny. It’s a performance that always leaves us looking for succor and compassion when we watch it. Brennan did similar duty for Hawks in To Have and Have Not, as a genial drunk who scampers after Bogie like a gimpy scarecrow, asking everyone he meets if they’ve ever been bitten by that damn dead bee. And he did it for Capra in Meet John Doe, where, as a character known only as the Colonel, he substitutes predatory “heelots” for Apis mellifera. We’re actually kinda fond of the Colonel, who’s like Ned Sparks without the urban flair. Grousers strike a chord with us; and you can’t get any grousier (or more chord-striking) than a guy who bitches about what a pain in the ass it is to work for a living. Not everything in life is sweetness and light, and we like a fellow who’s willing to point that out.

Unlike his harmless codgers, though, Brennan’s Bean is a mean old buzzard, with no redeeming qualities, although there’s something almost likable about him. The actor plays him as a ruthless charmer, with a husky laugh that seems to disappear in his chest while he makes it. But Bean’s also a cunning madman; he can quote the law to Jane-Ellen when she accuses him of murdering her farm hand, and he’s definitely not to be trusted: Note how, whenever he’s crossed, the humor fades slowly from his eyes, like steam off a mirror (Wyler’s long takes favor Brennan’s scary changes of expression in these scenes). Brennan did a similar turn for John Ford in the great My Darling Clementine, playing the head of the nasty Clanton bunch as a grinning psychopath. (He almost never raises his voice or makes a sudden move in that film, so it’s a shock when he takes a riding crop to one of his sons and whales the tar out of him.)

What’s unusual about Bean is that within him there’s a touch of the poet. It’s manifested most clearly in his obsession with the famous British actress Lillie Langtry (also a real, historical person). Bean has her posters and postcards plastered all over the wall behind his bar, as well as in his bedroom (her photos cover his mirror; perhaps that’s why he never shaves). For Bean, Langtry is an unreachable ideal, a goddess akin to nature: “I never met the sun, I never shook hands with the moon, and I never been introduced to no clouds,” he replies to a question if he’s ever met her. The questioner (Lucien Littlefield) is an unassuming dude-type who’s unaware of how deep the obsession goes. Airily remarking that he “never got around to seeing” Miss Langtry himself, the dude finds himself ejected from the bar by the enraged Judge.

The Muse’s Image: Langtry’s posters behind Bean’s bar. Toland’s cinematography highlights each one clearly.

The Jersey Lily (as Langtry was dubbed) is more than muse and divinity to Bean; she’s a fortunate source of inspiration to Cole when he’s trying to escape hanging on the horse thievery charge. Noticing the plastered images (they’re rather hard to miss), Cole insinuates he once met the actress and even obtained a lock of her hair. What follows is a chess match between Cole and Bean, as Cole (aware that the jury will reach a verdict once the members finish their card game and polish off a bottle of whiskey) leads on the credulous Judge, while Bean tries to bargain for possession of the precious lock. Brennan and Cooper’s timing in this scene is aces: Cole strategically withholds information as he sizes up Bean’s reactions; and the Judge is alternately eager and sullen, trying to feel out how much of what he hears is truth and how much is hogwash. Supposedly Cooper was not eager to make the film, because he thought Brennan’s character would overwhelm his; but his hesitation doesn’t show here. The two actors play their scenes like a great comedy team, their give and take making us laugh at the same time that we realize (as Cole does, in his gut) that friendship with the unpredictable Judge is deeply dangerous.

Saluting the Muse: Cole manages to save his (literal) neck by promising Bean a lock of Langtry’s hair. As the Judge downs his glass, Cole silently raises his to a poster of Lillie.

It’s that relationship between Bean and Cole that highlights for us the essence of the Western—male friendship. The real romance in The Westerner is between Cole and Bean; their initial encounter takes up nearly the first third of the film’s running time. Often in Westerns such friendship is laced with antagonism; the title character of The Virginian has to hang his best friend for cattle rustling. Similarly, Bean and Cole don’t trust each other (Cole compares Bean to a pet rattlesnake he once had—something you never turn your back on), but, unlike his relationship with Jane-Ellen, Cole shares something with Bean: A sense of male independence, a freedom from societal restrictions represented by Wife and Home. Jane-Ellen wants Cole to stay with her and settle down; but homesteading means being tied to one place (when she tries to persuade him that cornhusking is “fun,” Cole looks understandably dubious). The Judge, however, offers Cole space; the territory he lords over has plenty of room to move around in. Cole’s loyalties are divided; he’s sympathetic to both homesteaders and ranchers (he even warns Bean when homesteaders plan to lynch him). But, in the genre’s classic narrative pattern, Cole must eventually choose sides. A greater principle must take hold; and under such pressure, male bonds inevitably weaken. The protagonist must grow up, electing for growth and maturity over a perpetual, unrooted adolescence.

Male Camaraderie: Cole and Bean’s friendship has an element of challenge. Here they empty their bottles of rotgut into large beer glasses, each daring the other to finish the whole thing. Note how Coop and Brennan communicate by glances and facial expressions.

The choice happens for Cole when Bean orders his cronies to burn the homesteaders’ farms; it’s a measure of their friendship that Bean’s peculiar sense of honor forces him to admit the truth when Cole asks him to swear on Langtry’s lock of hair (actually Jane-Ellen’s). Appointed as a deputy, Cole then hunts down the Judge in a theater, where Lillie Langtry herself is appearing. Langtry’s theatrical appearance is the Judge’s apotheosis: he buys up all the tickets, dresses in his best (his old Confederate uniform, complete with cavalry sword), and seats himself in the first row. When the curtain rises, however, it’s Cole onstage, waiting for the showdown.

The film has built up our expectations for these two meetings—the final shootout between Bean and Cole, and the meeting between Bean and Langtry. And Wyler does not disappoint, staging the shootout in the theater as if it were part of the show. But with the Judge’s demise Wyler takes his film out of the territories of dusty realism and morality tale and into the realm of the poetic. Wyler stages the encounter between Worshipper and Goddess as a prolonged point-of-view close-up. Although mortally wounded, Bean insists on standing up when meeting his idol. Cutting from Bean’s shining face, Wyler focuses on that of Miss Langtry’s (Lillian Bond), who at first is unsure how to behave, and then reacts as any pro would when meeting a devoted fan. She smiles, angelically—

—as Toland darkens the space around her figure—

—until her image softly blurs out of focus…

In true Romantic tradition, the meeting with the Muse entails death; and on the soundtrack, as Lillie’s image dissolves from sight, we hear the Judge’s gasp, then the thud as his body falls. Only when his heart’s desire is fulfilled does the hard, seemingly indestructible Bean die. Wyler ends the scene with Cole, in long shot, departing the theater, while we watch the curtain’s shadow on the wall as it falls.

The real Roy Bean never met the real Lillie Langtry (he also, after a bout of heavy drinking, died peacefully in bed). As befitting the Western genre, though, Wyler gives us the myth, satisfying our desire as to how this story should end. Our own feeling is that Wyler should have stopped his film right there: The curtain fallen, the show over, and Cole wandering out to an unknown fate. But Wyler adds an epilogue, which itself adds another mythic feature to the film: The Western as embodying the myth of American History. There’s no post-modern cynicism or disillusionment in Wyler’s finalé. As another curtain rises (in this case, a window shade), giving us a close-up of a Texas map on a wall, Jane-Ellen and Cole, now married, watch a new group of homesteaders arrive for settlement. Bean’s death has cleared the way for another fulfillment, that of American destiny.

No matter. For us, The Westerner inhabits the land of epic Romance, where equally matched men battle to the finish, where poets salute their muses, and where the Goddess descends from the Machine to bestow a final blessing. Like Ford, like any artist, Wyler decided to “print the legend” here. And maybe he was following his own heart’s desire in doing just that.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Below are a series of screen caps illustrating points in our essay, as to how Wyler and Toland’s techniques of long takes and deep focus highlight narrative themes in The Westerner.

> WYLER’S USE OF STAGING AND SPACE WITHIN THE CINEMATIC FRAME – COLE HARDEN AS OUTSIDER:

Toland’s staging and use of deep focus inscribes the narrative’s themes onto the image: Brennan on left confronts Davenport on right (he’s just hanged her farm hand); standing in back and between them is Cooper, who’s been accused of horse theft.

Toland’s use of deep focus creates a dramatic long shot in depth as the ‘jury’ comes back with its verdict. Brennan and Cooper, flanking the bar (left and right), have their attention riveted on foreman Paul Hurst, entering from the back (and clutching a bottle). Charles Halton as the undertaker, on right behind Cooper, is already measuring Harden for his coffin.

Harden the Outsider: Wyler stages the action to emphasize Harden’s separation. Cooper enters screen left, while homesteaders Fred Stone, Davenport, and a young Forrest Tucker (behind Stone) cluster on the right. Davenport, as the object of Cole’s interest, stands beneath a light.

Harden the Outsider: Wyler stages the action to emphasize Harden’s separation. Cooper enters screen left, while homesteaders Fred Stone, Davenport, and a young Forrest Tucker (behind Stone) cluster on the right. Davenport, as the object of Cole’s interest, stands beneath a light.

Dramatic movement within the frame: The homesteaders leave in their wagons after their homes have been burned down. Cole heads in the opposite direction, but he looks back to watch them, emphasizing his psychological indecision.

> WYLER’S CINEMATIC REALISM:

ABOVE: the film’s recreation of Bean’s beat-up saloon. BELOW: the actual Roy Bean saloon in Texas. A bearded Roy Bean is seated center, on a cask, holding an open book.

Toland’s camera etches ridges of sweat on the neck of Cooper’s horse.

Forrest Tucker is overwhelmed by dust during a brawl.

A striking overhead shot displays the extent and ferocity of the fire that destroys the homesteaders’ crops and houses.

> DRAMATIC USE OF GROUPINGS WITHIN THE CINEMATIC FRAME:

Wyler stages conflicting interests in a group shot: The homesteaders argue whether to stay after the farm hand’s hanging. Seated in center (with arm in sling) is Dana Andrews, who opts to leave; behind him (back to camera) is an indecisive Tucker. Standing in the foreground, screen right, facing Andrews is Davenport (back to camera), who insists on staying. Fred Stone is seated far left foreground (back to camera).

Wyler uses Brennan’s figure as the focus of this shot, with contrasting vertical and horizontal lines. While his men cluster below him, Bean stands up alone, dominating the skyline.

Wyler again has Brennan dominate a shot as, standing center foreground (back to camera), he confronts the homesteaders who want to hang him. On left is Cooper; Tucker is in forefront on right. Note the gun that Bean has stashed in a back pocket; he’ll pull it at an unexpected moment.

As Bean orders the homesteaders out, Wyler frames him within a frame on left, created by the saloon pillars, while the homesteaders are in an ascending mass on right.

Toland again uses deep focus to emphasize the drama within a shot. Here a whiskey bottle commands front and center; once the jury members finish the whiskey, they’ll return a guilty verdict. In back is scowling foreman Paul Hurst; on left (in profile) is Chill Wills.

Let the Play Begin: The curtain rises to reveal Cole on stage, ready to confront Bean. The Judge in foreground (back to camera) rises from his seat in surprise. Toland’s use of deep focus clarifies the spatial relationship between the characters while creating a sense of dramatic confrontation.

————————————————————————————————————————————

BONUS CLIP ONE: Here’s a clip from The Westerner, showing Bean’s arrival at the theater and the dramatic rising of the curtain. Note how Wyler moves his camera when, as Bean seats himself, the camera rises up and pulls back for a spectacular overhead shot. (From his actions, Bean seems never to have been in a theater):

BONUS CLIP TWO: Here’s a series of scenes from 1929’s Hell’s Heroes; they give a good sense of Wyler’s visual style and use of moving camera. Notice in one scene how much dust an outlaw shakes from his hair. Also notice the robbery set-up scene, with one robber leading a horse across the screen, while the three other robbers ride up in the background:

vinnieh

/ June 25, 2012Wow what a really interesting article about a fantastic director. Your article was highlt descroptive and excellently well-written.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Glad you liked it – thanks for visiting and for your comment!

Sam Juliano

/ June 25, 2012This is quite a spectacular post on an essential Wyler. You’ve really given it the kitchen-sink treatment bringing all kinds of fascinating aspects and components, and a staggering screen cap presentation to boot. I wouldn’t even know where to start here, but suffice to say I completely agree with your preference as to Brennan characters that are most appealing to movie goers.

This is as about as definitive a post on this film as could possibly be written, and it’s a blogothon entry par excellence. Greg Toland’s cinematography is utterly magnificent.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Thanks so much for your comment! We found on repeated viewings of ‘The Westerner’ that it is indeed a visually rich film, due in large part to Toland, and probably an important one in Wyler’s filmography. We get a kick out of watching Brennan as Roy Bean – he’s as mean as they come, but still a charmer!

John Greco

/ June 25, 2012GOM – Masterful article here. I kind of say similar things about Wyler’s use of the camera, the deep-focus photography, in my upcoming look at “The Best Years of Our Lives.” He lets the audience decide where to focus their attention as opposed to Welles or Hitchcock whose camera said “look at this.” Admittedly, I like Welles and Hitchcock’s styles more but that takes nothing away from Willie.

The relationship between Brennan and Cooper is the heart of this film. Brennan steals the film but Cooper gives a fine subtle performance. I have to admit when the film strays away from these two and focused on Cooper’s love life or the war between the homesteaders and the cattlemen it slides into a cliché ridden bland story. Fortunately, as you point out, the real romance here is between Coop and Brennan who save the day. Truly enjoyed this contribution to the blogathon.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Cooper and Brennan work great together in this film. They seemed to have had a good chemistry; they’re also wonderful together in ‘Sergeant York’ and ‘Meet John Doe.’ We agree with your point about Wyler’s camera; it’s the argument made by Andre Bazin on using deep focus and mise-en-scene to achieve a greater reality in film. Wish more directors would use it today! Thanks for your comment.

Muriel

/ June 25, 2012This is one of the few movies I like Cooper in. Wyler squeezed some talent out of Cooper in this one. Touches of light comedy was Cooper’s forte. You mentioned that he was worried Walter Brennan would over shadow him. He was right to worry. When I think of this movie, I think of Brennan not Cooper. To me, Cooper has the charisma of a fence post. I just don’t see that “thing” he has for so many people.

There are a few directors where I always watch their films: William Wyler, Fritz Lang, Ronald Neame, Powell & Pressburger. Also, I always watch a film if the score is by Miklos Rozsa.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Yes, this is really Brennan’s film; his performance is memorable (although our own take on Cooper is very positive; we always enjoy watching him!). We agree that Wyler is a director whose films are always worth watching. Thanks for your comment.

Page (ACaryGrantFan)

/ June 25, 2012Thanks for defending Wyler and his work in such a beautifully written piece. IMDb often gets things wrong so I would consider the source. Also, thanks for listing Wyler’s very impressive resume where Westerns are concerned.

When you have Cooper AND Brennen on board with Wyler at the helm you can’t go wrong and it’s just as good as any Capra or Hawk vehicle for me. Beautifully shot with great attention to every detail. Wyler got things right with his cinematography and I won’t even get into how well actors flourished under his direction. (Okay Cooper could act under anyone but you get the point) Also loved the soft focus to fadeout of Lillie’s image.

Thanks for all of the great screengrabs with captions on what made Wyler such a brilliant director. It was like revisiting the film with new eyes!

A stellar review of a great Western (I prefer it over Stagecoach and Cimarron)

Page

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Thanks so much for your comment, Page – glad to know that someone else considers Wyler an auteur! It’s a shame that so many of Wyler’s silent westerns have been lost; they would probably add much to understanding him as a director (especially as he was directing in the silent period). Apparently his early talkie ‘Hell’s Heroes’ is on DVD; it really deserves a scholarly reading. We’re pleased that you liked our screen caps; they were exhausting but fun to do!

Patricia Nolan-Hall (Caftan Woman)

/ June 25, 2012It’s all true – everything you said about “The Westerner”. I didn’t see it the first couple of times I saw the movie and harshly decided it was my least favourite from Willy. The darn thing had to sneak up on me in its glory. You have put into perspective my purely emotional response, and I have a great appreciation for your article.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Thanks so much for your lovely comment! We had a similar experience ourselves – on first seeing The Westerner, some years ago, we didn’t think much of it. But on re-viewing it for the Blogathon, we really came to appreciate it as a great film and an essential Western. It makes you wonder why Wyler didn’t direct more Westerns during the sound era (especially as he did so many silent ones in the 1920s) – he might have rivaled even Ford.

R. D. Finch

/ June 25, 2012GOM, a splendid job on a Wyler film that’s one of his most interesting and undeservedly neglected, probably because it comes from his most fertile decade and is overshadowed by better-known works. You had so many pertinent and penetrating observations about the film (and other closely related subjects) that I don’t know where to begin a comment. So I will just point out some things about your typically detailed post that especially struck me:

The way you placed this film between “Hell’s Heroes” and “The Big Country.” The way you placed it in the context of the elements typical of the Western genre. Your extensive discussion of the visual element here and in all Wyler’s films, particularly his use of framing and staging to define character and situation. (Why this example of the collaboration between Wyler and DP Toland isn’t more often discussed puzzles me. The wacky expressionistic outdoor sets and photography, as in the burial scene you picture, especially are eye-poppers that at times had me thinking of “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”!) The Sheherezade-King style interplay between Cooper and Brennan that makes this such an unusual Western that points ahead to Wyler’s mythic approach in later films.

That discussion of Brennan was also superb. This is my favorite Brennan performance too, one that shows he was a more accomplished actor than one might suspect from the Grandpappy Amos-like persona he so often projected. I once wrote a post in which I said that his Roy Bean combines “his usual cheerful folksiness with psychotic megalomania.”

I’ll have to stop here although there’s much more I could add. I will say what an impressive and wide-ranging post this is while never straying from the subject at hand, and what a tremendous and much-appreciated contribution it is to the Wyler blogathon.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Thanks so much, Richard, for your wonderful, in-depth comment, and also for hosting this great blogathon. You make a perceptive point about Toland and Wyler’s staging approaching the expressionistic; and it’s puzzling, as you note, as to why Toland’s work with Wyler doesn’t have the attention as his work with Welles or Ford has, especially since Wyler’s style depends very much on depth of field and use of the whole film frame. Probably another reason why ‘The Westerner’ may be an overlooked film is that Wyler isn’t associated with Westerns (again, surprising, considering his early silent output); and maybe his film came too soon after ‘Stagecoach’ and not soon enough before ‘The Ox-Bow Incident,’ and so got lost between these other great Westerns. Yet his direction of ‘The Westerner’ indicates how deeply he understood the genre and its themes. Perhaps he should have directed more of them in the sound era (a Wyler version of ‘Shane’ is something we would have liked to see; it would have been his kind of material). Looking forward to reading all the other posts in the blogathon!

FlickChick

/ June 25, 2012Wow – this was an epic post – and just great! A wonderful examination of the film, it’s director and stars. And I’m with you – I liked Brennan as a bastard a whole lot better. As for Coop – what’s not to like? Just a great entry into the blogathon..

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012We’re keeping track of the anti- and pro-Bastard Brennan responses here, and so far the pro-bastard responses have it hands down. (Now there’s a future blogathon: “Bastards on Film” – George Sanders, anyone?) Thanks so much for your comment and for stopping by!

Ken Anderson

/ June 25, 2012I’m growing increasingly fond of your writing style, as your posts always entertainingly interweave information, insight, and a chuckle or two (the Decorative Smudge is a classic!)

i don’t have a lot of patience with the western genre, but I do like Walter Brennan a great deal. I may have to bite the bullet on this one (western analogy intended, at least as a show of good faith) and sit down to watch this. Thanks for another great post!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 25, 2012Thanks so much for commenting, Ken, and for enjoying the post. If you like Brennan, you’ll find he’s a lot of fun in ‘The Westerner’; if for nothing else, it’s worth watching for him (and it’s on DVD, so — hint, hint). Looking forward to your post on ‘Funny Girl’!

Brandie

/ June 26, 2012A truly fantastic post–one of the best I’ve read so far for this event. You have so thoroughly touched on every aspect of this film, and everything that makes it such an interesting entry in Wyler’s filmography. I particularly enjoyed the screen caps demonstrating Toland’s unparalleled cinematography–Wyler and Toland were an excellent team, and these shots really drive home the skill and care both of them took to give the film such a unique and effective look.

And again, thank you for the mention of the Doris Davenport article–we really appreciate it!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 26, 2012Thanks for posting the Davenport profile, it was very helpful! You might be able to make an argument for Toland as auteur of the films he worked on, his style is so distinctive; and when he worked with a like-thinking director like Wyler, the result is gold. Thanks for stopping by!

KimWilson

/ June 26, 2012Brennan and Cooper play exceptionally well off one another. I always viewed Bean and Cole’s relationship like a father-son one. I have to disagree about Davenport lacking star power. I think she stands up well against both Brennan and Cooper. Very informative post.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 26, 2012Cooper and Brennan seemed to have had a good onscreen relationship; they played in several films together and seemed to have established a good camaraderie. Unfortunately Davenport’s career was cut short by a devastating injury, and ‘The Westerner’ turned out to be her next-to-last film, so audiences were deprived of the chance to see how her career might have developed. Thanks for your comment.

Judy

/ June 26, 2012A wonderfully detailed posting with a fabulous selection of screencaps for good measure. I very much like your discussion of Wyler’s use of long takes and deep focus – ‘Counsellor at Law’ is another film where he uses this and allows the actors space within each scene, as you discuss. Must admit I haven’t seen ‘The Westerner’ as yet, but will definitely return and reread this posting when I’ve done so!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 26, 2012Thanks so much for your comment and for stopping by! ‘Counsellor at Law’ is a beautiful example of Wyler’s deep-focus style, and also of his superb work with actors (John Barrymore & Bebe Daniels are at their absolute best in this film). We hope you get to see ‘The Westerner’ soon (it’s on DVD), it encapsulates so many essential themes of the Western genre, as well as Wyler’s directing style; it’s also a good intro for anyone who hasn’t seen many Western films.

Kevin Deany

/ June 26, 2012I’m in absolute awe of this post, and feel like I need to go back to Film School 101 to ever write half as good as you do. Your post accomplished every film blogger’s dream – make one go back and watch the film in question. Which I plan to do very, very soon. An outstanding job!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 26, 2012Thanks so much for your lovely comment, Kevin! We’re glad that you want to see The Westerner again; it’s well worth several looks. Our own feeling in reading all the great posts on Wyler for the Blogathon is that we want to see so many of his films ourselves, either to catch up on ones we’ve missed, or to re-see those we already know, but with fresh eyes illuminated by all the wonderful essays we’ve read. Thanks for visiting!

Jon

/ June 26, 2012Wow this is a staggering piece of dissection and a great essay on Wyler…

“There’s a respect for dialogue, for the way actors speak and interact, for the expression of ideas. ” “What might be called, if not Wyler’s signature, then certainly a stylistic trait—his use of long takes and deep focus—was one that, by arranging actors within the frame and allowing them to act without interruption, favored the performer.”

These are some great points and echo my same feelings that I recently wrote about on The Heiress and Dodsworth. He really lets the performers work and create an emphasis on emotion and conflict. I haven’ even seen The Westerner, but must correct this error quickly. I know I will love it. Great screen caps by the way!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 26, 2012Thanks so much! Wyler seems to have wrought a kind of alchemy with his actors; so many of them are at their best in his films. Olivia de Havilland was never better than in The Heiress (and Ralph Richardson, playing her father, was magnificent). At a certain level, in spite of all the difficulties they may have had with him, Wyler’s actors must have trusted him in order to turn in such consistently great work. Hope you enjoy watching The Westerner!

Rick29

/ June 26, 2012GOM, this is one your best ever (and that’s saying a lot). I, for one, don’t think of Wyler as an auteur, but you make a good case, especially with his fondness for “literary” film, the long takes, and deep focus (all readily apparent in DETECTIVE STORY, which I just watched again). I also believe that he was interested in focusing on the characters and the story. Visual style can detract from that, even with a great director like HItchcock. For example, I think the visual flourishes in THE BIRDS dominate the film for most viewers (though not for me). Wyler would never let that happen.

Grand Old Movies

/ June 27, 2012It would make an interesting discussion as to whether Wyler can be considered an auteur, one who expresses a singular vision through a body of films. As Flick Chick noted in her own excellent Wyler post, Wyler was not one to flourish his obsessions or fetishes via his movies. And many viewers might not think that a consistent visual style would constitute ‘auteurism’ in the classic sense. You might argue that the visuals do express a certain point of view–for Wyler, a certain contemplative outlook on life, an encompassing view of humanity that allows characters to evolve onscreen in complex interactions. But the fact that the auteur question is brought up about him is an indication, we think, of the undoubted impact his work has on audiences. Thanks for stopping by, Rick, and also for your always perceptive comments!

Classicfilmboy

/ June 27, 2012Comprehensive post on a terrific film!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 27, 2012Thanks so much – glad you like the post and the film!

The Lady Eve

/ June 29, 2012GOM – What an amazing and thorough assessment of “The Westerner.” I realized as I read your piece that I haven’t seen this movie for – decades? – and what I remembered most about it was Walter Brennan’s Judge Roy Bean and his obsession with Lily Langtree. I have got to watch this one again, and soon…

I was very happy you took on Wyler and the auteur theory. His work may not be as instantaneously identifiable as that of, say, Welles or Hitchcock, and he may have worked primarily within the studio system but, as you point out, there are consistent qualities and features to be found. And aren’t versatility and artistic accomplishment as rare and singular as a particular personal vision?

Grand Old Movies

/ June 29, 2012Thanks so much for your comment and for your own terrific post on The Letter! Brennan gives his most memorable performance in The Westerner, and he deservedly won an Oscar for it; he’s also a lot of fun to watch. The non-auteur ‘ruling’ seems unfair to us (it seems in part to have come about because critics don’t like Ben-Hur). Wyler, as you note, was versatile yet consistent (which is definitely a rare quality); and we see his consistent use of long takes and deep focus as indicative of a personal point of view, one taking in human beings in all their complexity, and an interest more in viewing personal interactions than in technique for its own sake. It’s why Wyler’s films, we think, still resonate today.

shadowsandsatin

/ June 30, 2012What an epic post, Grand Old! I’m not a fan of westerns or, necessarily, of Gary Cooper, but I certainly want to see this one after reading your outstanding write-up. In addition to your insights, I also enjoyed learning about Lillie Langtry and Judge Roy Bean — and I greatly enjoyed your turn of phrases, like this: “Note how, whenever he’s crossed, the humor fades slowly from his eyes, like steam off a mirror” and this: “. . . a genial drunk who scampers after Bogie like a gimpy scarecrow, asking everyone he meets if they’ve ever been bitten by that damn dead bee.” Really good stuff!

Grand Old Movies

/ June 30, 2012Thank you so much for your comment and for stopping by! Even if you don’t like Westerns, we recommend The Westerner – it’s beautifully paced, has lots of interesting action, and a great performance by Brennan. We also think it’s a good film to become acquainted with the Western genre, because it touches so many basics. We did some read-up on the real Judge Roy Bean, and he was truly an eccentric and memorable character. Brennan really conveys that larger-than-life quality in his performance.

ladylavinia1932

/ September 14, 2012[“We tend to find The Big Country more bloated than big; it has a Message and clearly limned Good and Bad characters;”]

THE BIG COUNTRY is a bit bloated. But its characters are more than just “Good and Bad”. And the “Message”, I believe, was very effective. But if the 1958 movie isn’t your cup of tea . . . so be it.

Grand Old Movies

/ September 14, 2012À chacun son goût