Jassy is an enjoyably hokey 1947 Gainsborough historical-fiction film, sumptuously designed and costumed and lensed in picture-pretty Technicolor; but the best thing about it is Basil Sydney with a horsewhip. There’s something so quaint and old-fashioned about brandishing a horsewhip, redolent of periwigs, knee breeches, and club steps. I was reminded of what Groucho Marx once said, and waited for the horse to show up.

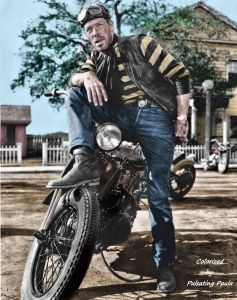

Looks like the horse is on his way…

Sydney plays a bad-tempered old sot in Regency-era England, and, to my reckoning, he horsewhips at least two people onscreen, but other whippees are suggested (when a mute servant wishes to identify Sydney, she picks up his horsewhip to do so). During one non-whipping moment he manages to win, in a dice game, a nice mansion off another sodden landowner (Dennis Price, in a dreadful wig), who had the misfortune to roll snake eyes on a crucial throw. When Price is later caught cheating trying to win the house back, he has no choice but to blow his brains out in proper ruined-Brit-gent fashion—the camera lingering long and steady on a shut door behind which we hear a Big Bang, but not much else. It may not be the most cinematic shot (in several meanings) in the film, but its point (like the bullet) does get through.

Before…

…and After…

By now viewers will also get the point of Jassy: People in cravats and crinolines behaving badly. Sottish Syd, for instance, does all your typically bad-tempered-sot things—drinking, wenching, gambling, losing at chess—and not even the acquisition of a splendid dwelling improves his temper (though he keeps his whipping hand in good shape). After his wife runs off with the interior decorator (!) hired to redo the joint, our Syd bullies his family and servants, plays patty-fingers with the kitchen maid, shoots a man in his cups (Syd’s, not the man’s), and in general behaves abominably. Even when injured in a horse crash (I guess it finally showed up), bedrid Syd persists in his abominable behavior, hurling his food to the floor, demanding strong drink, and scowling at all and sundry. Is it any wonder you enjoy watching him? I estimate that Syd and his lash raise this film’s enjoyment quotient by a good 40 percent. That’s a lot of wristy follow-through on one twitchy strip of leather.

The title character of Jassy herself, played by Margaret Lockwood, is much better behaved but unfortunately is held back by her dicey origins. The daughter of a gypsy woman, Jassy has inherited, via her family line, the ability of second sight (“They think my mother’s a witch,” says Jassy, airily adding, “she’s not, really”). What this means onscreen is that periodically Lockwood freezes in front of the camera, widens her eyes, and then screams—because she ‘sees’ something happening elsewhere at that moment. There’s not much one can do to ‘act’ clairvoyance, but Lockwood does what she can, expanding her eyes appreciably and riveting her gaze. Though even as a ragamuffin gypsy girl Lockwood has perfectly plucked eyebrows and an expertly applied light blush and lipstick, the latter coming through splendidly in Technicolor. But she does display dirty feet in one scene, which I’m all for; it provided a welcome bit of onscreen realism. Surely a glimpse at one’s physical soles can be as revealing as a look at the spiritual one.

For fans who favor this genre, I’m pleased to report that Jassy is your typical historical-fiction folderol, about how a lower-class heroine works her way up to the aristocracy (in this case, via marriage to Syd and his aristocratic horsewhip) by pluck, luck, and mucking about in kitchen tweenydom (the film does touch on the yucky realities of lower-class employment). She bucks it all to get possession of the house Syd won off Dennis Price so she can give it back to Price’s son, whom she secretly loves. Not much is new here, nothing you wouldn’t see in Forever Amber or Kitty or The Man in Grey, except for Jassy’s prim virtue and Syd’s horsewhip (which does make up for a lot). On hand are Patricia Roc, uninteresting as a bitchy rival, and the grandly overripe Ernest Thesiger, of Bride of Frankenstein fame, wasted as a mild milord who disapproves of card-playing. I’d love to have seen Thesiger wield a whip of his own; the enjoyment quotient would probably have been upped an additional 15 percent. But, alas, he remains sadly whipless. I suppose there were only so many horses who could show up.

The other best thing about Jassy is Margaret Lockwood herself. Lockwood is probably best known today, at least to American film audiences, as the spunky heroine of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, but she could switch to historical frou-frou if the role called for it. With her dark hair and eyes and pale skin, she also looked good in Technicolor. And her strong-boned facial structure, the way she angles her high-cheeked profile to the camera, suited her for those extravagant puffed hair styles and tilted hats so dear to modern designers of the Regency period. Her face had mobility and expressiveness and was receptive to the camera; you can ‘see’ what she’s thinking when she’s onscreen (no clairvoyance needed on the audience’s part). A face that catches the camera’s gaze like that is worth entire vistas of blandly sculpted perfect features.

Lockwood was a big star in 1940s Britain (I previously wrote about her as a modern noir anti-heroine in Bedelia), but it was more than her high-cheeked profile that made her so. Even when flouncing in petticoats and bodices she could bring out something hard-headed and practical, yet also sensitive, in her characters. When in one scene a prospective employer asks to see if Jassy’s hands are clean, Lockwood hesitates, her body rising up and stiffening from the indignity of the request. It’s a nice piece of observation, telling us much about who Jassy, deep down, is. I wonder if that’s why audiences, especially women, responded to Lockwood—because she understood that, beneath the laces and corsets, women still have to be tough in this world. Lockwood’s ladies may aspire to refinement but essentially they’re fighters (see her remarkable performance as a suddenly-wealthy Cockney widow facing down a killer in Cast A Dark Shadow). And Lockwood’s best scenes in Jassy are between her and Sydney’s sot, letting us see her how her character coolly negotiates the balance of power between compliance, ambition, and necessity. Just thinking, and writing, about that aspect of Lockwood’s, I’m starting to like her much more.

What Lockwood also had going for her is what David Shipman noted as the one thing great movie stars possess: a quality of stillness, of existing onscreen in and of oneself. Lockwood could keep parts of herself in reserve, only letting us see, in lightning glimpses, what’s roiling beneath. Such as the way Lockwood’s Jassy, when dismissed from a job at an upper-class girls’ school, takes her leave of one gushingly inane pupil. Lockwood plays the scene, a long take, fast and brisk, yet at one moment her Jassy flashes at the girl, and at herself, a mature, all-knowing smile, as if to say: You silly goose, you’ll never know as much about life as I do. We grasp it as a rare feeling of superiority that Jassy allows herself, but it’s also revealing of Lockwood, of something she did instinctively, from a perception deep within—and done with an actor’s imagination and understanding of both role and scene. That kind of intuitive flash may come but rarely, and Lockwood was gutsy enough to go with it. She made the moment count.

You know, I really do like this lady.

You can watch Margaret Lockwood, Basil Sydney, and Jassy here on YouTube (in a print that looks in serious need of restoration), while its availability lasts. Lots of viewing fun; bringing your own horse is optional.

Paddy Lee

/ July 14, 2020I love everything you said about Margaret Lockwood but my main takeaway from the entertaining article will be whipless Ernest Thesiger!

Grand Old Movies

/ July 14, 2020I always enjoy your comments, they’re the best! If anyone could have wielded a whip with panache, it would have been Ernest Thesiger, one of my favorite actors. And if you’re a Margaret Lockwood fan and haven’t seen Jassy, I highly recommend it for her (and if you have seen it, see it again for her and Basil Sydney!). Lockwood has such authority in this film, and has such an aura, that I can see why she was such a big star in Britain.

Carl-Edward

/ July 16, 2020Margaret Lockwood could do no wrong – a superb actress, and one of the most versatile I have ever seen. I recommend: ‘Love Story’ (1944) (her co-star here is the incomparable Stewart Granger); ‘The Wicked Lady'( 1945), a most engrossing story with a fine cast: James Mason, the beautiful Patricia Roc, Griffith Jones, and Michael Rennie, who falls hopelessly in love with Miss Lockwood; and: ‘Madness Of The Heart’ (1949), where she is convincingly blind for much of the film.

Grand Old Movies

/ July 17, 2020Yes, I agree, Lockwood was an excellent, versatile performer, and always hit the right tone for her characters – I’ve seen all those films you mention, and she’s good, in different ways, in all of them. She doesn’t seem so well known today, but she’s an actress who deserves to be remembered.