Some time ago my brother, an avid reader of my blog, called me up to tell me of an idea for a blog post.

“Listen,” he said (or words to that effect), “I have an idea for your blog.”

“What is it?” I asked (being one, I flatter myself, always open to suggestion).

“Miscast actors,” he replied. “Playing roles that don’t fit them.”

“Terrific,” I said (or words to that effect). “Do you have a film in mind?”

He sure did.

Hence—

—the subject of this post: The Oklahoma Kid.

Heard of The Oklahoma Kid? It’s a 1939 film from Warner Bros., coming out the same year as Gone With The Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. That’s mighty heady company there. Kid itself was part of a Warners’ trend away from those short, punchy, urban tales like Little Caesar, 42nd Street, Marked Woman, and Kid Galahad the studio had been known for in the early 1930s, towards longer, glossier, more upscale melodramas, often with an historical setting—stuff like Captain Blood, Jezebel, The Life of Emile Zola, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex and Dodge City, which was a western that actually cost a million dollars. That’s right, saloons and sagebrush, but with table manners.

Like Dodge City, Kid was a western. And, like Dodge, Kid was no cheapo B-oater, but was an A-level production, with a name cast, imposing sets, a score by Max Steiner, cinematography by James Wong Howe, a sprawling story set during the 1893 Cherokee Strip Land Run, and, to boot, a portrayal of President Grover Cleveland.

As far as I know, this is the only movie that includes President Grover Cleveland as a character.

I admit, I was impressed. When it comes to cinematic Presidential portrayals, Hollywood usually doesn’t go beyond a canonical few—Lincoln, of course, the two Roosevelts, sometimes Washington and Jackson, more recently Kennedy—but there’s a whole list of White House holders that remains unexplored. So it’s nice to see a Cleveland pop up here, replete with bushy mustache, bulging waistcoat, and seemly gravitas. Must’ve been an interesting fellow.

However, Grover Cleveland is NOT what The Oklahoma Kid is known for.

Go Into Your Dance

No, what the film is famous for its egregious miscasting of James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart in the leads. I yield to no one in my admiration for Cagney and Bogie, but these actors were 20th-century urbanites, down to their capillaries. They’re right at home where there’s concrete, hard-boiled dames, and the sound of screeching tires. But in a 19th-century western? Where the sagebrushed plains of 1890s Oklahoma spread out to meet the horizon where the west commences? That’s the last place I’d think to find these two asphalt-bound desperadoes, their 1930s Noo Yawk accents lodged in their nostrils. They don’t sound right. Cagney spills out words a mile a minute, while Bogie alternates between stiff-lipped mutters and seething growls. “Moider,” he says (or growls) when talking about one, sounding at such moments like a male-drag Thelma Ritter. It jars the ear. I kept expecting one of them to order the other of them to be taken for a ride. And not a stagecoach one either.

But it isn’t just the sound. It’s also how these two guys look. It’s more than their gangland struts, how they sashay about like a pair of public enemies in a petrified forest. Their bodies, their very movements, don’t fit the landscape. That’s when it hit me why so many tall actors—Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, John Wayne, Joel McCrae, James Stewart, Henry Fonda—look so at home in westerns. They’re not overwhelmed by that vital factor: the Horse. When you got a western, you got a horse; and when you got a horse, you got a guy sitting on it. And there’s a meaning in that.

Now, when Randolph Scott mounts a horse, he places a foot in the stirrup and swings a long leg up and over the horse’s back with a lazy grace that’s beguiling to watch. And when he sits on the horse, those same long legs reach down so far that he can keep them casually bent at the knee. The result looks relaxed yet strong, the great Scott retaining easy control of that mighty beast below him. You’re not aware of any effort needed to get on and stay in the saddle because Man and Equine look so natural together.

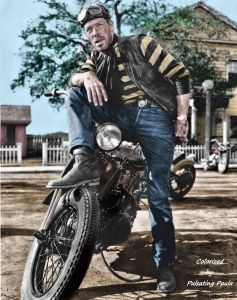

Whereas when Cagney gets on a horse, he has to grab the saddle and pull his body up into the air before he can place his foot in the stirrup and then hop into place. It’s like a kitten scrabbling atop a wolfhound and hanging on for dear life. Cagney could, and did, ride horses (he raised them on his farm), but that’s not the point. The point is that when Cagney gallops onto a mountain landscape and the horse rears up in heigh-ho-Silver fashion, you hope this small boy won’t fall off that huge animal. Even the movie notices: while one character diplomatically refers to Cagney as a “little fellow,” Bogie bluntly calls him a “squirt.” Squirt is not a content-neutral word. It’s got a whack that you feel. And if the scriptwriter needs to inscribe the lead actor’s lack of height into the dialogue, as a kind of meta-comment on what audiences may be thinking, then you know someone at Warners was aware of something being a wee bit off here.

He’s hanging in the air here.

About the only short actor I know of who looked good in a western was Alan Ladd; and that’s because Ladd knew how a gunslinger should stand. Which is—still. Perfectly so; weight on one foot, one hip relaxed, the classical contrapposto style. He also knew how a gunslinger should walk: contained, slow, measured, aware how each step on the ground could be his last. The tall guys in westerns, the Scotts, Fondas, Waynes, McCraes, Coopers, also knew this. Once the chaps and dungarees and holsters were on, their bodies adjusted. They became weighted, steady, conscious of treading the earth, yet conscious of the lightness needed in the legs and feet. Because you never know when you’ll need to move fast.

Who knows if gunslingers out west really did move like this? But that kind of motion seems to go with the territory. I think these ideas of how such 19th-century people moved may have come from 19th-century photographs, in which everyone is still and dignified and a bit stiff—in part because of the unfamiliarity, and slightly scary technology, of photography (the subjects are consciously trying for ‘dignity’), in part because of photographic film’s then-slow exposure times, so poses had to be held for several seconds. And I think in large part that dignity we perceive arose from a sense of brevity. Life was shorter, harder, tougher, and people got older faster. You had to grow up more quickly, so as to to survive. The experienced gunslinger showed that, in his walk, his stance, his cool, steely gaze. It’s only the brash green kid who moves like a jerk.

Cagney doesn’t move like a jerk, but he moves like Cagney. Meaning he struts and bounds across the screen, buoyant yet restless, his hands flicking like nervous birds. Oddly, unlike his gangster films, he can’t control his energy here. He’s always rushing forward, springing, sprinting, bouncing like a ball. My God, Cag, I found myself thinking, didn’t you ever watch Randolph Scott? Or Coop or McCrae? The center of gravity should be low. Keep the weight back, the shoulders relaxed, the hips firm, the heels down, and the belly IN. But Cagney skips on the balls of his feet, he pushes his upper body forward and his lower back in, and he won’t keep still. Jamming a thumb into a front-door bell, he’s like a kid impatient for a child friend to come out and play (when he wanders into a saloon, I half-expected the bartender to ask for ID). And when Cagney aims a pair of pistols at an enemy, he does that antsy shoulder twitch he used when playing gangsters. For a hoodlum, that looks cool; for a shootist, that wastes time. A real gunslinger would have plugged him right then, taking him unawares.

It’s more than Cagney being short and fidgety. He was dainty, fine-boned, strangely childlike in shape. He had a toddler’s figure, with small shoulders and a belly thrust out from a curved back, so that the tummy bulges between belt and holster. Western clothes don’t look right on that childish form. And that matters, because men in westerns wear a surprising amount of clothing and equipment: boots, gun belts, holsters, bandannas, hats, vests, spurs, chaps, as well as dungarees and cotton shirts. That’s a lot of fabric and hardware, and it just buries Cagney. The hats are too big (Bogie notoriously said that Cagney looked like a “mushroom” under his 10-gallon hat, and he unfortunately was right), the holsters too clunky, the boots too thick and high, and the spurs too weird on Cagney’s small feet (you need to keep the HEELS DOWN for spurs, old man). Urban suits can be bulked out and slimmed down with shoulder pads and pinstripes, but cotton shirts can’t. And gun belts hang too low on short men; you have to be well-proportioned like Alan Ladd to carry it off. When that big hat slips down over Cagney’s eyes, he looks about as mean as Shirley Temple.

Yet Cagney still is Cagney. He’s mesmerizing, never dull, and he has beautiful, sexy, bedroom eyes. Whenever onscreen, he always seems to be coming from somewhere and to be going somewhere; he exists in the moment but a whole history clings to him. To every scene he brings that sense of an inner dialogue; his eyes have depth, they think. “Lovely morning,” he says to Rosemary Lane as he’s escorted out the room with a gun barrel shoved in his back. As he speaks he glances back and down at the weapon, and in his eyes are blended humor, cockiness, and a fully aware irony. Even if he moves wrong, he still moves like no one else ever could. A fun scene has Cagney singing “I Don’t Want to Play in Your Yard”; annoyed by Ward Bond, he flings a punch that flies out like knuckled lightning. Then he goes right back to singing, eyes closed in unruffled bliss. At such moments, Cagney can’t be matched by anyone on the whole dang planet.

I shouldn’t gripe so much about The Oklahoma Kid. It’s an entertaining film (even if I found myself laughing in the wrong places). Bogie brings intensity to his role while trying not to look embarrassed, though he does tend to grip his gun belt as if he’s afraid it’ll fall off. (He also slumps. You can slump when you’re Sam Spade in a trenchcoat, because you’ll look cool and subtle and a little reserved, and a trenchcoat does wonders for figure flaws. But a slump in a cotton shirt is just a slump.) The supporting cast is strictly second-tier Warners, but I enjoyed Charles Middleton as a lawyer; what better role for Ming the Merciless?

And the horses are magnificent. They’re big and strong and sweatily beautiful, with the nobility of kings. And how nice of them to give rides to the kiddies.

BONUS CLIP: James Cagney croons about not wanting to play in your yard, while Ward Bond interrupts and Humphrey Bogart sneers in this snappy scene from The Oklahoma Kid: